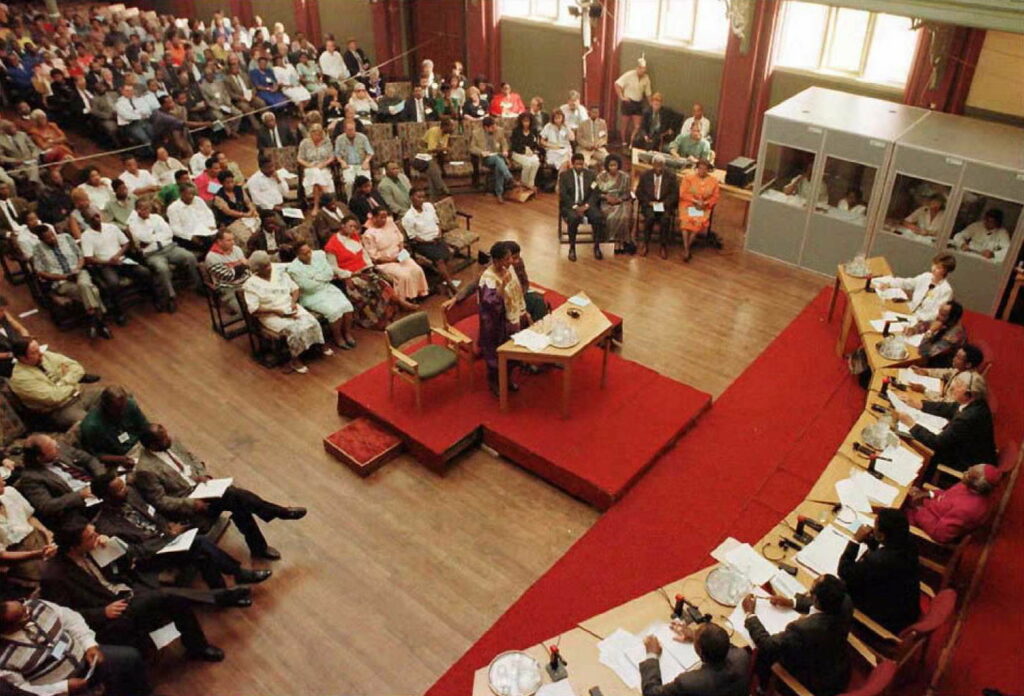

Nomonde Calata’s tears as she testified in court last month about her husband’s assassination 40 years ago echoed the raw anguish heard during South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings after apartheid ended in 1994.From 1996 to 1998, the TRC heard harrowing accounts of murders, torture and other apartheid-era abuses from hundreds of victims and some perpetrators, aiming to expose the horrors and begin healing.Internationally hailed as a model in reconciliation, 30 years later its reputation is tarnished at home, where critics say the exercise allowed some to get away with their crimes.Calata was one of the first to appear at a hearing. In her mid-thirties, she told of the 1985 assassinations by police of her husband and other anti-apartheid activists known as the Cradock Four, one of the era’s most notorious cases.She recounted the story again this year in June at a new inquest, still seeking justice and closure, this time supported by lawyers from the “Unfinished Business of the TRC” programme of the Foundation for Human Rights (FHR), a non-profit organisation.Set up by the July 26, 1995 “Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act”, the TRC heard about 7,000 applications for amnesty from perpetrators of gross human rights violations from 1960 to 1994, the year white-minority rule ended.It rejected most, including for six apartheid policemen who confessed to involvement in the Cradock killings, and recommended criminal prosecutions for 300 cases where there was no full disclosure or when the acts did not have a clear political purpose.But only a handful of these were pursued. Claims that follow-up was deliberately squashed, including by politicians in the post-apartheid leadership, led President Cyril Ramaphosa to appoint an enquiry in May.With many perpetrators now deceased, the FHR hopes the investigation will uncover who blocked prosecutions and make them accountable instead, the group’s executive director Zaid Kimmie said. “So it would not be the original perpetrators,” he told AFP. “But where people in the democratically elected post-1994 government interfered with criminal prosecutions, we hope that those people in turn will be pursued for the role that they have played in the miscarriage of justice.”The TRC was a compromise for the “move forward without further bloodshed, without a civil war,” Kimmie said.”Did it wipe away the antagonisms and the hurt that accumulated over the previous centuries? No, it couldn’t do that,” he said.- Failure – Of around 20,000 written witness accounts submitted to the TRC, more than 2,000 were heard in televised hearings open to the public. The process exposed the “full brutality” of apartheid as well as “some very hard truths” about anti-apartheid groups, said Verne Harris, who was a member of the TRC team. “Its most important achievement was to make any form of denial impossible — denying the state terror, denying the special formations that were put in place by the apartheid state to assassinate activists and so on,” he said.Reconciliation needed “big symbolic interventions” such as the TRC and a new national anthem, Harris said.”But then you also need the hard work… and this is where we failed so miserably,” he said.South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world, with the high unemployment rate of more than 30 percent disproportionately affecting blacks along with crime and poor service delivery.”People started becoming first cynical and then very angry. And so reconciliation for me, that project has failed,” Harris said. A national dialogue announced by Ramaphosa and to be launched in August is a “revisiting” to take stock and develop a roadmap for a new era, Harris said. But, “it’s not about a national conversation. It’s about the political will to actually implement,” he said.- Narrow focus – The TRC’s narrow focus on single acts did not tackle the “structural violence” of white domination, from land dispossession to economic disparities, said Keolebogile Mbebe, lecturer at the University of Pretoria.And South Africans are not a unified nation, she said, citing stark differences between population groups, from opportunities to where they live. “We keep saying ‘South Africans’ as if we’re talking about a group of people who are homogenous, like Springbok supporters,” she said. “You can have Springbok supporters in the stadium, but just remember, when the match finishes, you’re going back to different ‘countries’,” she said.