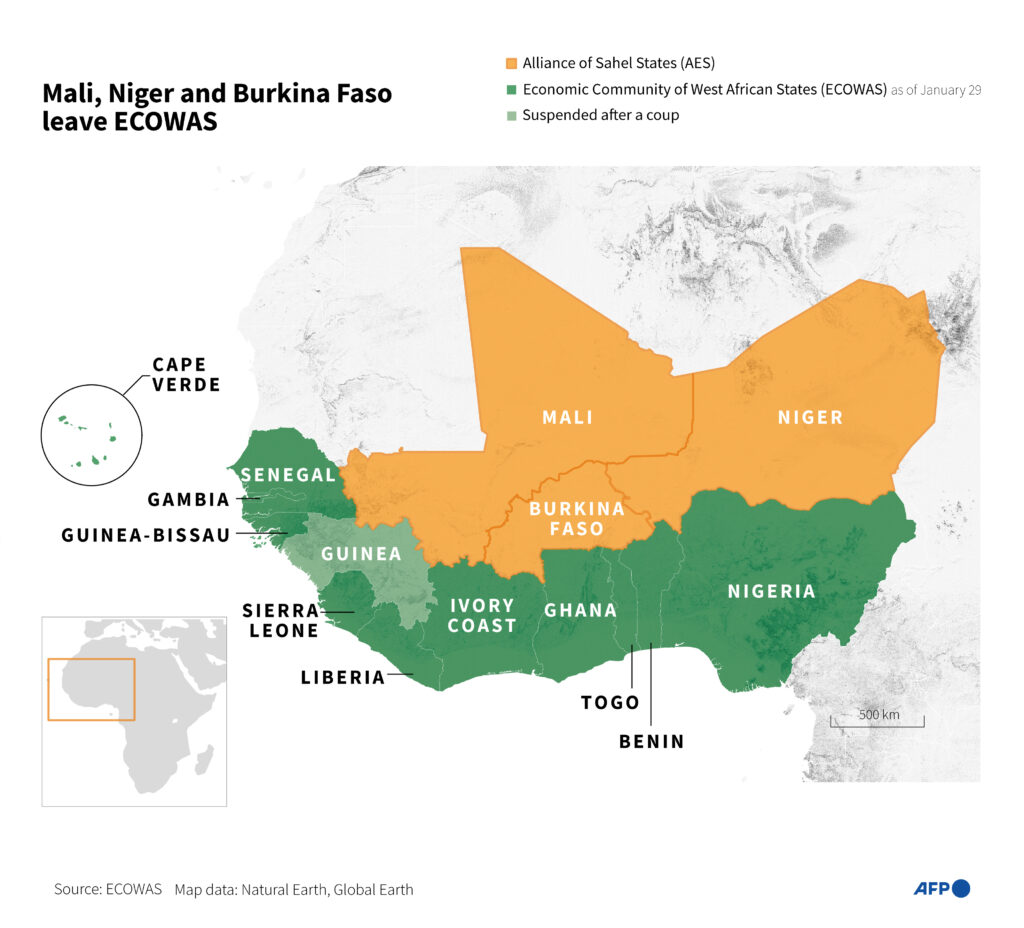

Junta-led countries Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso officially left West Africa’s main political and trade group ECOWAS on Wednesday after more than a year of diplomatic tensions.The withdrawal has shaken the Economic Community of West African States, which many consider to be the continent’s most important regional group and this year marks its 50th anniversary.While its leadership said in a statement that the group would “keep ECOWAS doors open” to the three countries, their departure has left the organisation’s future uncertain.The rupture was sparked by the July 2023 coup in Niger, after military leaders in Burkina and Mali had also seized power since 2020.ECOWAS threatened to intervene militarily in Niger to reinstate the deposed president and imposed heavy economic sanctions on Niamey, since lifted.The three countries, who were founding members of ECOWAS, announced in January 2024 they planned to withdraw immediately, but the rules of the organisation required one-year’s notice for it to take effect.”ECOWAS remains open,” Omar Alieu Touray, head of the ECOWAS bloc, insisted at a news conference in Abuja, the Nigerian capital, where the bloc has its headquarters.He had invited representatives of the three countries to a technical meeting “to initiate the withdrawal formalities”, he added.”We look forward to those discussions.”- Separate confederation -Their military rulers accused ECOWAS of imposing “inhuman, illegal and illegitimate” sanctions.Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have now formed their own confederation, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES).The ECOWAS statement called on member countries to recognise “until further notice” passports from the three countries bearing the ECOWAS logo.Citizens of the three countries should “continue to enjoy the right of visa free movement, residence and establishment in accordance with the ECOWAS protocols” until a new decision is taken, it said.Goods and services from the three will also be treated in line with ECOWAS rules until the West African group decides its “future engagement” with the three, it added.And Touray told journalists in Abuja: “Any state can decide to come back in the community at any time.”The military leaders in the Sahel states accuse ECOWAS of failing to help them fight jihadist uprisings in their countries and of being too close to France, the former colonial power in the region.All three have largely cut their security ties with France, turning towards Russia, Iran and Turkey for assistance.In a sign of the doubts within ECOWAS, Togo and Ghana have normalised relations with the three states and Ghana’s new president, John Mahama, has named a special envoy to the Alliance of Sahel States.